1 min

1 min

In recent years, two new concepts have emerged, providing both food for thought and a basis for action, to ensure that buildings no longer suffer from the climate but begin to evolve with it: adaptation and resilience. But what exactly do they mean? How do they differ? And above all, what do these concepts mean in practical terms for construction and renovation solutions? And where does decarbonization fit into this?

Adaptation and resilience: what are we talking about?

Adaptation means planning for the negative effects of climate change and taking appropriate measures to prevent or minimize the damage they may cause, or to take advantage of opportunities that may arise.

So adaptation is not limited to responding to extreme weather events: it also involves rethinking the design, construction, and management of buildings to cope with gradual climate change (rising average temperatures, changes in precipitation patterns, etc.).

The resilience of a building is defined as the combination of its resistance, adaptability, and ability to recover from climate shocks and stresses. A resilient building is thus able to absorb shocks without losing its function.

This resilience is based on three pillars:

- Robustness: resistant to damage (reinforced structure)

- Adaptability: continues to operate despite constraints (backup systems)

- Recovery: quickly returns to normal (modularity, repairability)

In Miami, the Miami Forever Bond program, passed in 2017, will ultimately raise $400m, nearly half of which ($192m) will be dedicated to resilience in the face of rising sea levels and flooding. With drainage pumps, infrastructure elevation, and protection of critical areas, the goal is to transform a city that is regularly threatened into a region that can continue to function even during extreme events.

But resilience is not just a question of spending hundreds of millions of dollars in Western cities. In South Africa, the rural Lapalala Wilderness School proves that resilience can be achieved in other ways: to regulate temperatures in a tropical climate, wooden shade structures and native vegetation cover the outdoor areas, the walls are made of local earth to help filter heat, and the building is self-sufficient in water and energy. This model school welcomes 3,000 students per year and demonstrates that resilience must be adapted to the local context.

See also:

Building and renovating in a different way

Incorporating adaptation and resilience issues requires the construction sector to transform its practices with the aim of enabling buildings and infrastructure to continue to fulfill their roles in an uncertain climate.

Importance of choosing the right materials and solutions

Adapting the building envelope to temperature variations, particularly heatwaves, requires work on the performance of both opaque and glazed walls, taking several parameters into account: thermal insulation, inertia, solar protection, reflectivity, and surface greening.

The structures must be able to withstand extreme climate conditions, which requires innovation in the field of construction chemicals. The Trysfjord Bridge in Norway, the world’s largest cantilever bridge, uses lightweight aggregates that combine low density with high strength, exceeding the limits of traditional materials.

Renovating while incorporating adaptation and resilience

In developed countries, 80 to 90% of the buildings that will exist in 2050 have already been built. Adapting this huge building stock without demolishing poses a major technical, economic, and social challenge: working on occupied buildings, reinforcing aging structures, and integrating new uses without interrupting activity.

This logic transforms adaptation into precision work, on different scales. At the urban level, public spaces are becoming multifunctional: in Copenhagen, Tåsinge Plads square functions as a living space on a daily basis, but is transformed into a retention pond during extreme rainfall due to its permeable surface.

In the residential sector, the FORTIFIED standard in the United States reinforces the envelope of existing buildings against hurricanes – roofs, openings, multi-layer waterproofing – with convincing results during recent storms, limiting damage and speeding up the return to normal.

Knowing how to simulate different risk scenarios

A third lever complements these physical responses: data. Sensors, medium- and long-term climate scenarios, artificial intelligence, and digital twins enable a shift from a reactive approach to a preventive approach: predicting failures, simulating extreme scenarios, and guiding investment before damage occurs.

Singapore has invested $73m in Virtual Singapore, a digital twin used to test urban cooling strategies and enhance climate resilience. New York and Los Angeles rely on these tools to model flood and heat-island risks and target the most vulnerable infrastructure.

See also:

5 ways to make cities more resilient right now

Helping cities make better decisions

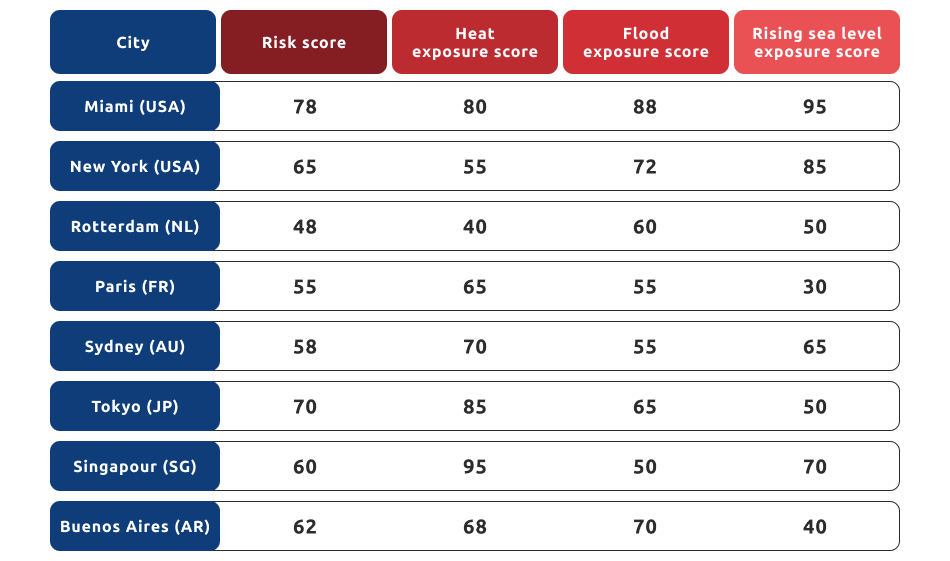

How can cities guide their adaptation policies if they have no data to measure the risks they may face?

It was to meet this need and enable decision-makers to be more proactive in their adaptation strategy that the Urban Adaptation Assessment (UAA) was created in the United States by the Kresge Foundation and the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative (ND-GAIN). This interactive database compiles data from more than 270 cities in the United States with populations exceeding 100,000. It provides a measure of how much a city is threatened by extreme heat, flooding, or rising sea levels. It also assesses its response capacity: does it have the institutional, financial, and technical means to protect itself and adapt?

See also:

Resilience: when cities are too heavy

The indicators enable comparisons to be made, guide investment, and justify priorities. Measurement becomes a lever for action, but the responsibility to take action remains political. Between two cities with equal exposure, it is the willingness to plan ahead that makes the difference.

And where does decarbonization fit into this?

Adaptation and resilience do not detract from the goal of decarbonization; on the contrary, they directly contribute to achieving it. A building capable of withstanding climate shocks is a building that does not need to be rebuilt in a hurry, does not need constant repair, and avoids the massive emissions associated with each disaster. Carbon reduction is no longer just an issue at the design stage. It also has a role to play in the building’s ability to last, remain functional, and survive crises without generating new peaks in emissions.

Decarbonization is thus changing its time scale. It is no longer limited to the initial optimization of materials or systems, but is part of the long-term life cycle. Investing in robust envelopes, adaptable structures, and preventive solutions can reduce the carbon footprint in the long term by avoiding demolition, reconstruction, and premature replacement

Source: Adapting Buildings to Climate Change, Collaborative report from Arup & Saint-Gobain, 2025

See also:

Climate hazards: how to make cities more resilient

Towards greater adaptation and resilience: the essential role of the insurance sector