8 min

8 min

Nowadays construction must meet the demands of sustainability. What is your approach to sustainable construction?

Benedetta Tagliabue: In architecture, it’s, first of all, about finding a good reason to create things. The history of this discipline is brimming with examples of fights to be able to carry out construction or development work. A characteristic of human intelligence is its ability to pave a way through the impossible, to find answers that we weren’t thinking of. The role of architects is to use this ability to seek out what’s difficult. The smart way to find new pathways is to observe nature. You can learn a lot from it in terms of strategies, especially when it comes to responding to climate change. Each time I contemplate old buildings, I realize the difficulties, time, and strength it took to build them. Whatever the resources and materials available at the time, for the most part, their presence is still relevant. In this respect, historic architecture is extremely sustainable out of necessity.

How can we learn to deal with climate change?

B. T.: We are at a very critical moment, but I think that it is not necessary to be alarmist or a prophet of doom. We must use our intelligence to face up to this crisis, even if paradoxically it is what has brought us to this point. I really like to experiment and discover new techniques, it’s wonderful. But I realized that in fact there is nothing new about sustainable materials, as we have already been using them for a long time. I remember the day when I discovered the word “original”, which means something exceptional, associated with innovation, but also refers to being at the “origin”. What we think of as an original material has often been there from the beginning; it is already known.

What material, for example?

We often work around textures, such as fabric. It’s a very old technique shared around the world. At the World Expo Shanghai 2010 in China, we designed a wicker pavilion for Spain. I discovered that this material and technique were also shared by all of humanity. It’s like a universal language. Even if it is complicated to use it as a construction material, we are able to experiment with and test this technique combined with sustainable materials. All this is based on ancient craftsmanship.

Your material of choice is ceramic. What are its assets in terms of construction?

B. T.: A collaboration with an artist from Barcelona led us to take an original perspective on ceramic and develop a new approach. This fantastic, extremely old material – seen as too mainstream in the 1980s and the 1990s and thus no longer corresponding to the esthetic of the time – has enormous potential when it comes to thermal, water-repellent, and esthetic properties. So much so that it has become architects’ material of choice. Perhaps we should gradually reintroduce ceramic? We have rediscovered it. Lots of our projects use it. At this particular time of climate change, wood and ceramic are materials with which we can innovate, thanks to new technologies and a reinvented esthetic.

There’s also the glass that you use a lot…

B. T.: It doesn’t let light through… Glass is a very special substance – whose raw material comes from the earth – resulting in a particular chemistry, with a high capacity for transparency and protection. Don’t forget that glass was the secret of Venice, a city that I love more than any other. Glass technology is highly advanced, but the product still remains extremely mysterious today; it is therefore important to continue to experiment with it. As to its use, it is very positive. Many buildings are made of glass. But, on the one hand, there is the esthetic question and, on the other, the idea that at first sight a city with only glass buildings would not be sustainable.

Also, we always use glass combined with other materials. As it is a material that is constantly evolving – while it lets light pass through, it is also designed nowadays to protect us from it – we must use it with a great deal of discernment and insert it into our projects in a balanced, functional way. For example, buildings’ orientation is important. We are taking part in a competition for a subway station project in Prague (Czech Republic) that includes a large glass roof. It’s a magnificent city, but it lacks light in winter. For this reason, many public spaces are covered in glass, which offers enormous possibilities. With specific treatments, it can even produce integrated photovoltaic energy…

And, once again, it is possible to take inspiration from age-old methods, like in Bologna in Italy, where almost all the city’s streets are lined with arcades…

B. T.: Arcades are a great invention. We think that it’s normal, but it’s fabulous because they provide protection from the heat and cold simply thanks to the very structure of the buildings that shape the city. An arcade is an in-between place, between the private and public space. We are near the door of the house, but it is not the street and we are sheltered.

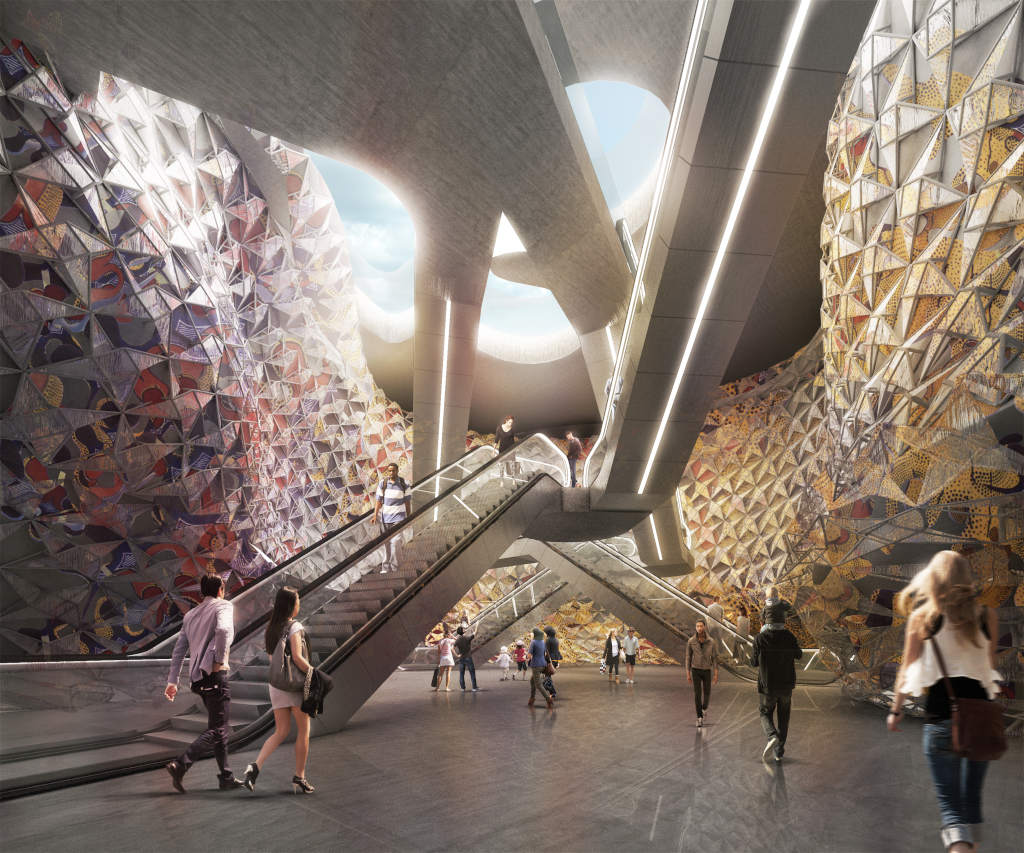

You describe the spirit of your work as: “Outside space is also home.” Could you explain why?

B. T.: I’m not a fan of buildings strictly separated from the outside. Instead, I like this utopia of a construction designed like the protection of a tree. Being slightly in the tree but also outside. For instance, we drafted a project for a building containing the smallest possible housing units. Our idea was not to design a building but a large roof to house activities, featuring a place to get together, meet, go shopping, and thus reduce the footprint of the whole complex in the neighborhood. This is the mindset with which we have approached the Clichy-Montfermeil (France) railway station project in the Paris region, which will be completed in 2026. The station’s exterior is a public space that reflects the residents. The buildings are covered by a translucent pergola that opens up a natural light well to the subway platforms. The walls are also important: the residents of Clichy-sous-Bois and Montfermeil will color them. A mural will be created by the French artist JR. In this way, we are touching the earth with a work of art. It is architecture that reflects the people who live there, designed like a large ballroom where they can come together. We may own our apartment, but outside belongs to us, too. The aim is to encourage a kind of appropriation in order to feel good where we live. And if we feel good, we behave well. It’s the basis of our societies.

You mean that to prioritize inhabitants’ health and well-being, we would need an architecture that is less protective and compartmentalized and more porous between inside and outside?

B. T.: In Clichy-sous-Bois and Montfermeil, there is obviously a social problem. The public authorities are in agreement about tackling it. This is why a project must be acceptable for society. As I said, people must be able to make the place their own as if they were at home. It is not an outdoor setting that has been imposed by the powers that be. We must be mimetic rather than domineering, and work with the images of a town that already existed. We often studied the esthetics of the market. How people get there, what they do there… How can we ensure that the station is in keeping with the town and the life all around it? We held workshops with women from Clichy-sous-Bois and Montfermeil and asked them to choose the texture that symbolizes their home country. It was an incredibly rich exercise. They made their choice and began to resize different pieces in their own way, which inspired us in designing the pergola and the inside of the station.

Do you think that esthetics is a lever for encouraging sustainability?

B. T.: Yes. But it’s more than that… It’s people’s soul. I’m absolutely obsessed with this concept of feeling at home. We design a lot of public spaces and I always try to ensure that people feel as if they were at home. It’s important. Our way of life today means that we are outside more often. The subway, street, city, etc. are places where we must feel protected.

Is this “just like home” a constant in all your projects?

B. T.: To a certain extent, yes. Out of the projects that have punctuated my career, I learned a lot from renovating Santa Caterina Market in Barcelona. It wasn’t just about refurbishing a market but rather the urban regeneration of the neighborhood, which lasted ten years. The Spanish pavilion at the World Expo in Shanghai was also very important. First of all, we had to build with a fabric material and a wicker frame – it was very new – which cannot be used in a lasting construction but is interesting for a temporary pavilion. It allows me to consider repeating the exercise with a more durable technology. In other words, attempting to combine the technologies of the countryside and the city. In the “just like home” spirit, we designed a small building for Sant Pau Hospital in Barcelona, a concept that comes from England, where some hospitals are not very hospitable… hence this place where you can relax, similar to certain rooms at home. With this in mind, we recently built San Giacomo Apostolo Church in Ferrara (Italy). Although it is more spiritual architecture in this medieval city where art is an integral part of everyday life.

What are your latest projects under development?

B. T.: We are extremely proud of Centro Direzionale subway station in Naples (Italy), which is being finalized: it is an experimental project that uses wood in a very harsh environment of concrete, glass, and iron. As Spanish architects have the distinction of also being landscapers, we are working in the port of Hamburg (Germany) to regenerate and urbanize the banks of the Elbe in the city center. This work is spread over 25 years. Finally, we are in the middle of building a seafront in Rimini (Italy), with a large green promenade just behind the beach. As I said, inside and outside form a whole to create a feeling of well-being.

* The Global Award for Sustainable Architecture was created in 2006 by architect and researcher Jana Revedin, with Paris’ Cité de l’architecture et du patrimoine as cultural partner. The aim of these awards is to promote innovation and experimentation with new types of design.

Photo credits: © Thomas Hampel, © Roland Halbe, © Shen Zhonghai © Marcela Grassi, © EMBT, © Paolo Fassoli, © Toni Ricard-Alta