7 min

7 min

With the ability to adapt to their specific geographic and cultural features, Valencia, Grenoble, Stockholm, and Ljubljana are delivering a string of remarkable examples when it comes to urbanization that is healthier, cleaner, and better adapted to tomorrow’s issues. They are conducting their ecological transition closely in line with citizens’ lives.

Bringing nature back to the city

Named European Green Capital for 2024, Valencia is aiming to become climate-neutral by 2030. To achieve this, the municipality has taken drastic measures to increase natural solutions and promote biodiversity. 97% of its 837,000 inhabitants live within 300 meters of urban areas with a low building density – gardens, parks, lakes, etc.

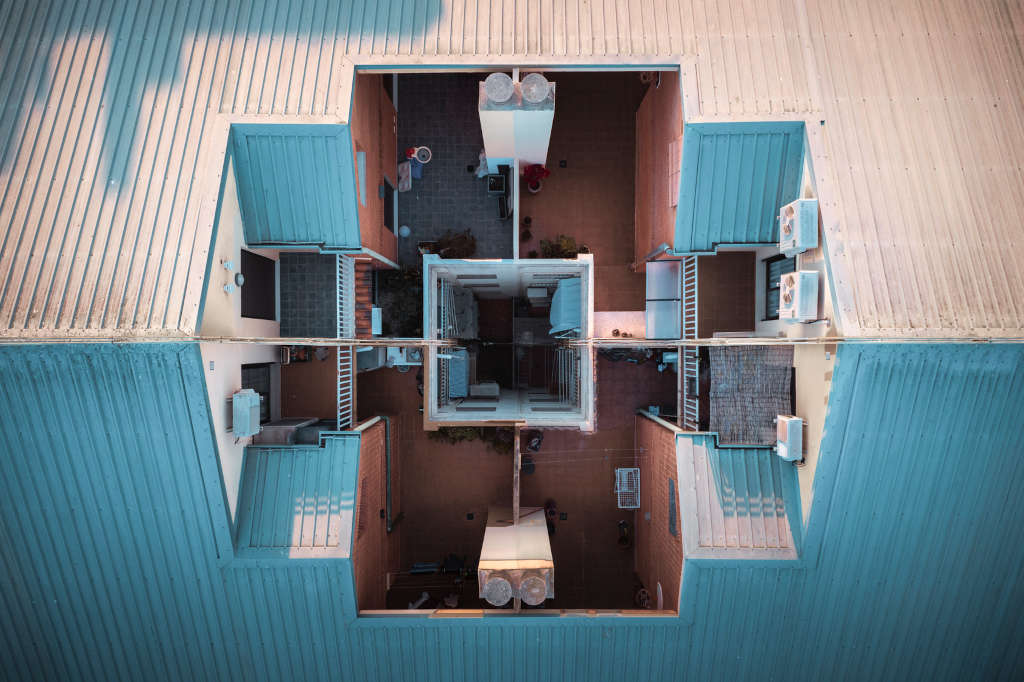

Stockholm, Ljubljana, and Grenoble, respectively Green Capitals in 2010 (first prize awarded), 2016 and 2022, are adopting the same approach, implementing a host of actions to create green spaces and revitalize former wasteland. This strategy creates new neighborhoods, designed to promote residents’ health and quality of life, such as the Flaubert eco-district in Grenoble. Pierre-André Juven, Deputy Mayor in charge of Urban Planning and Health, explains: “The urban planning approach taken in Flaubert, which we intend to roll out across the whole city, reflects the need to take into account the question of residents’ health.” In this former industrial district, nature is all around nowadays – the city planted more than 70 trees and created a five-hectare park – right to the heart of the housing blocks: on the roofs with 700 m2 dedicated to urban agriculture and on the ground with the creation of 13 communal vegetable gardens. These areas represent the lungs of the neighborhood, limiting the effects of global warming.

Reinventing mobility

If these cities are so pleasant to travel around, it is because they have successfully met the challenge of totally transforming mobility behavior. In 2007, the Mayor of Ljubljana, Zoran Jankovic, made the radical decision to do away with cars, at the risk of displeasing the inhabitants. Sixteen years later, fears have dissipated: the city center is as lively as ever but much quieter. “Heavy traffic is nothing but a distant memory,” states Zoran Jankovic. “Today Ljubljana is beautiful and organized. Open solely to pedestrians and cyclists, the city center is like a large salon, a cultural and social space.”

Of course, a green city is synonymous with eco-friendly alternatives to motorized transport. All these cities have a self-service electric bike hire system, a broad network of safe cycling paths, and extensive bicycle parking facilities. In Stockholm, the city-center trains and buses run on electricity or biofuel, leading to a 25% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions since 1990.

Spain’s third-largest city, Valencia is a haven of calm and greenery perfect for leisurely strolls. David Moncholi Badillo, Valencia’s Director of Mobility and Transport, is proud of the progress made, readily evoking the concept of the “15-minute city”, whereby people can access all amenities within a quarter of an hour on foot or bicycle from their home: “The 15-minute city is a way for people to reappropriate the urban space and meet their mobility needs while encouraging social and economic interactions. Today, 68% of travel within the city is done using sustainable modes of transport and over half of travel is on foot.”

Building and renovating… sustainably

To reduce their environmental impact and provide their inhabitants with enhanced comfort, the cities have put building energy renovation at the heart of their urban planning programs. Valencia is banking on self-sufficiency with the creation of three “carbon-neutral districts”. The idea is to provide citizens’ associations, businesses, and institutions with assistance to create “local energy communities” to renovate housing and implement a transition to renewable energy.

In Stockholm, within the framework of the European “Grow Smarter” project, the low energy district Valla Torg benefited from a large-scale renovation of residential buildings belonging to the public housing company Stockholmshem: exterior insulation, air intake control, exhaust air heat pumps, heat recovery from wastewater, energy-efficient elevators, presence detection lighting, photovoltaic panels, etc. Renters were even invited to install a home energy management system to help them optimize their consumption. Overall, the measure has led to a 76% reduction in the buildings’ total energy consumption and savings of up to 78% on the heating bill.

In Grenoble’s eco-districts, many new buildings are constructed using bio-based materials such as wood or earth. This bioclimatic architecture gives the buildings an authentic character while encouraging the natural ventilation of housing thanks to a double orientation. A project designed to promote biodiversity and freshness.

Creating smart cities

To accelerate their ecological transition, it goes without saying that the four European Green Capitals have relied on new technologies. Named “the Smartest City in the world” in 2020, Stockholm has capitalized on the use of data. Using sensors installed on public thoroughfares, the municipality can measure how busy routes are and implement more effective transport policies. “We previously had to wait one or two years to obtain the data; nowadays, we have it in just 15 minutes,” explains Stanley Ekberg, Client Executive at IBM Sweden. The residents of Valla Torg eco-district enjoy technological innovations, with a refuse collection system equipped with optical sensors and buried high-pressure tubes that reduce the coming and going of garbage trucks. A smart city is also a city connected to its citizens. Each Grenoble resident can track their energy consumption online, monitored by a multi-fluid energy sensor that compares it to similar households. This scheme then establishes a customized action plan to reduce energy expenditure and even offers guidance from an advisor. Like its peers, Valencia has developed a mobile app allowing residents to communicate directly with the municipality, receive notifications regarding work, incidents, etc., and carry out various administrative formalities remotely.

Differences based on geography and culture

Despite a broad common set of solutions, these four exemplary cities have successfully adapted their ecological transition policies to their specific circumstances in terms of geography, governance, culture, or heritage. In this respect, Valencia, the Mediterranean, emphasizes protecting marine ecosystems: the city is restoring dune ecosystems and wetlands to renaturalize the northern coastline. Nestled in the Alps, Grenoble is facing serious climate changes that are forcing it to reinvent itself: the municipality, the metropolis, and the university have therefore formed an independent Green Capital & Transition scientific advisory board to gain a better understanding of the climate transition and its impacts on health. With its many islands and waterways, Stockholm has put a great deal of effort into protecting water resources. The water there is so clean and pure that the inhabitants can eat the fish caught in the city center! Last but not least, Ljubljana, at the forefront of natural disaster management, has worked hand in hand with its Balkan neighbors to share its solutions, particularly during the severe floods in Central Europe in 2014.

Valencia, Grenoble, Stockholm, and Ljubljana show us that it is possible for cities with a population of over 100,000 to effectively reconcile economic growth, quality of life, and environmental protection. Their efforts are brilliantly in line with the goals of the European Union’s Green Deal, which – as well as looking to put a stop to greenhouse gas emissions – wants to turn Europe into a just and prosperous society, boasting a modern, competitive economy with efficient resource management. To achieve this, the Commission also proposed stricter rules in 2022: a reduction in the annual limit value of air pollutants, more efficient urban wastewater treatment, protection of surface and ground water from new pollutants, etc. The ball is in the court of the Green Capitals, along with all European cities.

* The European Green Capital award was created by the European Commission in 2006. Every year, it is bestowed on a European city with more than 100,000 inhabitants, which is demonstrating its ability to achieve high environmental targets, is engaged in an ongoing and ambitious sustainability drive, and can serve as a model to inspire other cities. The European Commission relies on 12 indicators to determine the winning cities: air quality, noise, water, sustainable soil and land use, waste management, nature and biodiversity, green growth and eco-innovation, climate change mitigation, climate change adaptation, mobility, energy performance, and environmental governance.

Photo credits: © AmazingAerialAgency-AdobeStock, © Mikel Dabbah-Shutterstock, © Alexander Farnsworth-iStock,© Dima Anikin-AdobeStock,© skazar-AdobeStock, © DEA / G. ROLI-GettyImages, © Philippe Chancel